“Frustration is a cover-up for something we have yet to face in ourselves.” -Joan Chittister.

I’m still uncovering my cover-up. Frustration has a long, illustrious history with me that continues to play out every day.

I learned frustration from my culture. I was taught to strive. We strive to do better, to get smarter, to achieve more, to be more. If your history is like mine, the “do better and be more” was never clearly defined, but we were to strive for it nonetheless. We live in a society that promotes improvement, progress, moving forward and upward. I was taught implicitly that no matter how good I am, I should be better. I should not be content.

I learned frustration from my culture. I was taught to strive. We strive to do better, to get smarter, to achieve more, to be more. If your history is like mine, the “do better and be more” was never clearly defined, but we were to strive for it nonetheless. We live in a society that promotes improvement, progress, moving forward and upward. I was taught implicitly that no matter how good I am, I should be better. I should not be content.

I learned frustration from my church. The church promoted a variety of mixes messages that combined God’s grace with American striving. I was taught that I was loved beyond understanding, but also that I was a sinner that needed to do better, be more vigilant. Grace was a gift, but I’d better keep trying to improve anyway. You get the idea.

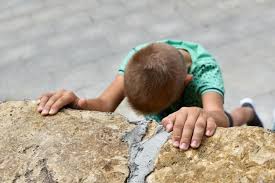

I learned frustration in my family. I took on the role of emotional care-giver. No one really gave me that job, but my older brother did the heavy lifting with actually being in charge of younger brothers. As second in line, it seemed my job to make sure everyone was happy and that mother was OK. After all, she held it all together. As a young boy, I had no idea how to do that job, but that did not stop me from trying, mostly through worrying and not making trouble myself.

From all those contradictory messages and vague expectations, frustration became my go-to feeling when things were not quite right but nothing was terribly wrong.

But frustration is a contrived state. It is a default rather than a choice. I want to make it more of a choice. That is my Lenten goal. I want to become more aware of the many ways I hide behind my frustration, allowing it to keep me from making a choice of how I feel and what I do.

0 Comments until now

Add your Comment!