-a sermon preached at First Presbyterian Church, Baird, TX. 9-20-20

“It’s just not fair!” How many times have you heard children shout that at the end of a game that didn’t turn out the way they wanted. I heard that at the end of every argument that ended with one of my children being grounded. How many times have each of us thought that when we listen to the news or have a conversation about some social, political, or financial event where a group we are not a part of appears to get a more favorable treatment than we think they deserve.

And of course the normal response, and the lesson we all have to learn eventually, is that life is not fair much of the time. It only seems fair when things turn out the way we want them to turn out. Even then, it often feels like we’re getting by with something.

Many of Jesus’ parables are stories that are not fair by the normal standards we use to judge fairness. It’s not necessarily fair that the shepherd would spend so much time and go to such risk for one lost sheep and neglect the 99 that are safe. It wasn’t fair to the older brother when the younger brother returned home after squandering his fortune, and the father threw a huge welcome home party. Many of the parables about the kingdom of God leave us scratching our heads because they are often not fair and reasonable according to how we typically think.

The parable about the laborers (Matthew 20: 1-16) is one such parable. This one has baffled me my whole life, and I’m in good company. It has baffled scholars since the first telling of the story. I consulted a lot of commentaries and interpretations that explain this story in a variety of ways. Some were simplistic, some far to complex and theological. None of them were very compelling, and each seemed to have the implied message, “We don’t really know.”

Jesus’ parables have stood the test of time because embedded in each of his stories are lessons about spiritual development, about God’s love, about social justice, about our own self-understanding, the list goes on. One remarkable truth of Jesus’ parables is that there are layers of meaning that can be useful to any level of spiritual understanding.

The story involves a landowner who hires workers at different times of the day. The situation of the landowner seeking workers was an event everyone listening would have understood. In Palestine, the grape harvest ripens towards the end of September, and then very soon after that, the rainy season comes. If the harvest is not gathered before the rains, it is ruined. So to get the harvest in between the ripening and the ruining is a frantic race against time.

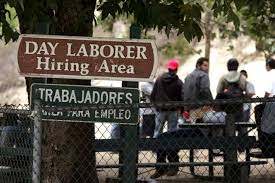

In Palestine, the market place was the place the hiring was done. The men who were standing in the market place were not street corner idlers. Workers came there first thing in the morning, carrying the necessary tools waiting to be hired. The fact that some were there early in the morning and some were still there late in the day was an indication of how desperate they were to work.

In Palestine, the market place was the place the hiring was done. The men who were standing in the market place were not street corner idlers. Workers came there first thing in the morning, carrying the necessary tools waiting to be hired. The fact that some were there early in the morning and some were still there late in the day was an indication of how desperate they were to work.

These workers were daily laborers who depended on landowners to hire them. They and their families were at the mercy of those daily wages from chance employment, and they were in danger of starving if they went a few days without being hired. Showing up each morning in hopes of working from 6 in the morning until 6 in the evening was their routine.

Let’s look at what typically happened. The landowner would first pick those workers who were familiar, who were known to be capable and dependable. If more workers were needed, he chose from among those who at least appeared most capable and eager. That was the first crew.

But later in the day it became clear to the landowner that more help would be needed to finish the day’s task, so back to the marketplace. The landowner then chose from among those who remained at the middle of the day. They had not been chosen by other employers, they were perhaps older, did not appear as strong or durable, but they had been patient and eager. So the second and third crews were picked as the day wore on.

With one hour left in the workday, the landowner realized he needed more workers to finish the task before the end of the day, so back to the marketplace. There he finds the leftovers, those who had waited patiently all day, and perhaps those, who because of dire circumstances, had shown up late. These were the old, the disabled, the addicted, those who had been detained because of a family crisis, those with no discernible skills or experience. These were the least of the workers. But the landowner chooses a crew to finish out the day.

To each crew he promised a day’s wages. How curious that he promised the same to the workers who labored all day, those who worked a half-day, and those who worked only one hour. Those who had worked 12 hours were hoping to make more money when they saw that those who worked only one hour got the full wage, but that did not happen. All got the same amount as was promised at the beginning of each shift.

So what do we make of this? This is not good finance. This is not a good hiring practice. This is not the way to build morale. This makes no sense. This is not “fair.”

This is not fair if you read this parable the way I do, from the perspective of the ones who were chosen first, selection based on all the qualities we see as desirable. Most of life in our society, in business, in politics is like choosing up sides to play sandlot baseball. You choose the players who can hit, who can catch, run, throw, and do all the things that will help you win, and it helps if you like them.

This is not fair if you read this parable the way I do, from the perspective of the ones who were chosen first, selection based on all the qualities we see as desirable. Most of life in our society, in business, in politics is like choosing up sides to play sandlot baseball. You choose the players who can hit, who can catch, run, throw, and do all the things that will help you win, and it helps if you like them.

You have to read this parable from the perspective of those who were chosen last to get a whole new meaning.

Jesus seems to be saying, “We’re not talking about money here. We are not talking about dividing people up the way the rest of the world does it. We are talking about the kingdom of God, about grace, about compassion toward others. These workers were not paid according to their effort, their skill, or their likeability. They were paid according to their need. What good would it do to pay one hour’s wage to the man who, through not fault of his own, could only work one hour. That would not feed his family, and it would demoralize the worker.” Jesus saw the worth of the person as independent of any of the measures we use in our daily business.

Jesus’ ministry was focused on eliminating the social, economic, and political criteria we use to evaluate one another, the many ways we divide people into categories. Jesus, through his teachings and through his example, turned that evaluation system on its head. Theologian Walter Wink wrote, “It is the poor whom God blesses, the meek and brokenhearted and despised who will inherit the earth. It is the merciful not the mighty, the peacemakers not the warriors, the persecuted not the aristocrats who will enter in the joy of God.”

And it is the task of God’s family, the church, to continue that mission. And this will always put the church at odds with society and the political system if we are truly doing the work we are called to do.

Fairness is not the issue when the need is desperate. Lately it seems we are surrounded with desperate need. The pandemic has changed the lives of more than 200,000 families just in this country, the forest fires and the hurricane have left thousands with nothing, the violence on our streets has everyone on edge and taking sides. Jesus never questioned the motives of people who came to him in desperation. He only questioned the motives of the religious, the wealthy, and the comfortable.

I saw an example of this early one morning at the conclusion of a breakfast program I help with. We had just provided breakfast to about 70 people, and as we were cleaning up, one of the men approached our team and said, “You know some of these guys are scamming you. They don’t need breakfast. They have homes and jobs and are just taking advantage of you.” I immediately began thinking of how we could evaluate those who showed up to make sure we were serving those with real needs when Charlie, the one on our crew who fixes the biscuits said, “We don’t care. We serve breakfast. We don’t care why they’re here, we don’t ask questions. Our job is to provide breakfast to whoever shows up.” That’s the parable in a nutshell.

But there is also another way, a more personal way to look at this parable. Jesus’ parables can always be brought up close so we can find ourselves in the characters. I find myself several times in this particular parable.

If you are like me, I strive to be in the first crew. I put my best foot forward, show my strengths, my competencies, my favorable attributes. I want people to like me, choose me, want to be with me whether I am applying for a job, preaching a sermon, or ordering coffee at the café.

I don’t want them to see the parts of me that would only get chosen for the second crew, and I certainly don’t want them to know the parts of me that that are needy and damaged and would only be selected for the final hour’s work.

And yet we all have those parts of ourselves that we try to keep hidden, buried, out of sight. We never lead with those parts of ourselves who are only capable of that last hour’s work, the parts of ourselves that are crippled, hurt, scared, angry, vengeful, envious, petty, and embarrassed. We lead with our capable and likeable selves and hope that no one sees those other parts of us.

But remember, grace is not ours because of our capabilities but because of our need, not because of our public selves but because of the parts of us that we don’t want others to see. So we sit in the marketplace, on the end of the bench staring at our shoes. The day is almost done, we’re hoping to be chosen, but doubtful we will be. But then we hear the words, “I choose you. Come with me.”

0 Comments until now

Add your Comment!