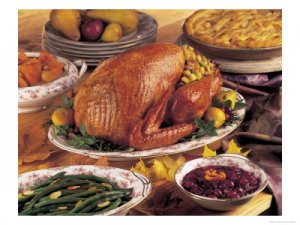

Thanksgiving has come and gone, but some thoughts about gratitude remain along with the leftovers. I find it easy to give thanks for a steaming, savory turkey surrounded by dressing, sweet potatoes covered with pineapple and tiny marshmallows, hot buttered rolls, and pumpkin pies. I have more difficulty with the turkey sandwiches, sweet potato remnants, and crusty dressing that endure far beyond the last piece of pie.

Thanksgiving has come and gone, but some thoughts about gratitude remain along with the leftovers. I find it easy to give thanks for a steaming, savory turkey surrounded by dressing, sweet potatoes covered with pineapple and tiny marshmallows, hot buttered rolls, and pumpkin pies. I have more difficulty with the turkey sandwiches, sweet potato remnants, and crusty dressing that endure far beyond the last piece of pie.

That’s often how Thanksgiving is for me, being grateful for the obvious, for those things that make me feel good. I have more trouble being grateful for events that are painful, disappointing, tragic, or even boring. Of course, this kind of selective gratitude is not reserved for Thanksgiving Day only. It’s true most of the time. There are so many things in my life that don’t fit easily into the gratitude categories. Consequently, after awhile selective gratitude starts to feel a little hollow.

According to Christianity and most of the world’s great religions, we are to be joyful and grateful in all things. That sounds all well and good until the alarm goes off in the morning. Then things get complicated.

For Christians, it was the Apostle Paul who stated this principle most clearly. Near the end of one of his letters, he rattles off a list of things for his readers to remember. It reads a little like a letter you’d get from your parents, “Remember to say thank you to your hosts, share your toys, brush your teeth.” Paul then says, “rejoice always, be thankful in all circumstances.” Excuse me; did he say “all circumstances”?

Paul was either out of touch of the kind of lives we live, or he knew something about gratitude that we don’t. Since this is coming from a man who was threatened, beaten, run out of town, stoned and left for dead, and spent several of his Thanksgivings in the county jail for preaching in the town square without a permit, maybe he knew something.

I am far from being able to live in perpetual gratitude, but when I look at my selective gratitude, I get some clues. Selective gratitude is based on judging a situation and comparing it to what I expect, what I want, what I’m comfortable with, or some other pet category. If the situation fits into one of those categories, I’m grateful. If not, I start complaining.

The problem with this approach is that we assume we know far more than we really do. In selective gratitude we assume we know how things will turn out. We assume we know the difference between what we want and what we need. We believe we are good judges of other people. We assume all kinds of things that often lead to being dissatisfied, disappointed, disillusioned, and a bunch of other disses. Little room for gratitude.

I’m beginning to think that this idea of being “thankful in all circumstances” fits with all the other outrageous things that the great religions teach us, such as loving our enemies, serving the least among us, and going to the back of the line instead of pushing for the front. Perhaps we are supposed to begin with gratitude, compassion, humility, and generosity rather than first judging a person or situation as being worthy or unworthy of those responses.

Starting there saves me a lot of mental wheel-spinning and emotional hand-wringing, and it opens up a vista of possible responses.

Years ago, when I was jogging regularly, there was a hill on the country road I chose as my course. Every day I got to the hill just as I was getting tired. At first I approached the hill as if it were an enemy. I panted, “Oh God, a hill,” as I trudged forward. After a few weeks I decided to change my approach. The hill became a challenge, and I declared, “Oh good, a hill,” as I forged on. Finally, after a few more weeks, I began to see it for what it was. Each day as I began the uphill run, I said quietly to myself, “A hill.” No judgment. I was simply grateful to be running, and this was just a part of my course.

Years ago, when I was jogging regularly, there was a hill on the country road I chose as my course. Every day I got to the hill just as I was getting tired. At first I approached the hill as if it were an enemy. I panted, “Oh God, a hill,” as I trudged forward. After a few weeks I decided to change my approach. The hill became a challenge, and I declared, “Oh good, a hill,” as I forged on. Finally, after a few more weeks, I began to see it for what it was. Each day as I began the uphill run, I said quietly to myself, “A hill.” No judgment. I was simply grateful to be running, and this was just a part of my course.

Printed in Abilene Reporter News, December 4, 2011

0 Comments until now

Add your Comment!