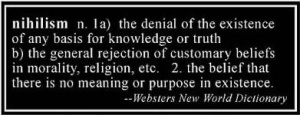

“I am a nihilist,” Austin declared during one of our conversations around the fire. In the three days together in this remote, idyllic cottage, our conversations had run the gamut from serious to silly, personal to global. This statement did not surprise me. I’d heard it before. One of Austin’s closest friends, a professor of philosophy, studies Nietzsche and is a self-professed nihilist. And it wasn’t a bomb he dropped to shock me. We had just listened to a podcast on his cell phone in which nihilism was discussed as a recurring theme throughout history, particularly among a younger generation disillusioned with their parents’ world.

We could have argued about his statement, but instead we began talking about differences between my generation and his. My generation grew up in weird times: post-Eisenhower and early-Kennedy optimism, post-assassination disillusionment, landing-on-the-moon patriotism, Viet Nam conflict and protests, and Woodstock/flower-child enthusiasm. Through it all, though, we were the baby boomers. We were convinced that life was going to get better and better.

Austin is growing up in a world with not so much promise. He was 12 when 9-11 happened, and the precautions and paranoia that followed have been a part of his normal life. He pays attention. School shootings are part of normal news day. He understands the implications of climate change as well as the implications of our not paying attention to it. He reads about Iran’s nuclear threat and Korea’s immature and impulsive dictator. He has opinions about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. On a personal level, he has been harassed and assaulted by the police because of his appearance. He identifies with those who put their hands up and shout, “Don’t shoot,” whenever an officer approaches. He has piercings, tattoos, and an “I film the police” t-shirt. The music he writes and plays is dark, loud, cynical, and unintelligible to me.

There is little we wholeheartedly agree on, but fortunately we can talk about almost anything. I can’t identify with his daily life, his schedule, and his friend base. But then, he would have nothing to do with my daily life. But it is our job, as father and son, to figure out how to make these differences work.

After some discussion, I stated, “I guess I am a nihilist, too, but not in the classical sense.” Since I frankly don’t know much about nihilism, I was following his definition. To paraphrase, I followed with, “I no longer believe there is an inherent purpose to life. I used to when I was your age, but I don’t anymore. We all live, we all die, and it’s only a matter of time until each one of us is completely forgotten. No trace. However, I do believe it is the responsibility of each one of us to determine our own purpose for living.”

We were both facing the fire. It was a chilly evening, the fire was warm, the Sam Adams Octoberfest was smooth. He made no comment, just continued to rock in his chair.

I knew there was more to him than a simple cynical nihilism. There was plenty of anger and distrust in the establishment, but I had observed some things that stood in sharp contrast to his philosophical label. For example, last winter he gave his heavy coat to a man on the corner holding a “Please Help” sign. It was a bitterly cold day in Illinois and the man had only a light jacket. Austin observed, “He was shivering and had tears in his eyes.” Austin figured the guy had a greater need for the coat, and Austin was in a better position to buy another one when he needed to. After one of our dinners out, he tipped our server 40% because, he said, “Servers have to take care of one another. We all know how much we depend on tips.” In one of our moments together he told me about verbally and then physically defending a homeless guy from a drunk and abusive patron. “First time I ever punched anyone. Bill (the homeless guy) says, ‘Thanks, man,’ every time I see him now.”

I knew there was more to him than a simple cynical nihilism. There was plenty of anger and distrust in the establishment, but I had observed some things that stood in sharp contrast to his philosophical label. For example, last winter he gave his heavy coat to a man on the corner holding a “Please Help” sign. It was a bitterly cold day in Illinois and the man had only a light jacket. Austin observed, “He was shivering and had tears in his eyes.” Austin figured the guy had a greater need for the coat, and Austin was in a better position to buy another one when he needed to. After one of our dinners out, he tipped our server 40% because, he said, “Servers have to take care of one another. We all know how much we depend on tips.” In one of our moments together he told me about verbally and then physically defending a homeless guy from a drunk and abusive patron. “First time I ever punched anyone. Bill (the homeless guy) says, ‘Thanks, man,’ every time I see him now.”

With those thoughts in mind, I continued. “For me, the world just works better if I do what I can to make it a better place. That means being kind to others when I can, particularly those who don’t seem to deserve it, and trying to do some good for those who most need it. That seems better than being mean and not caring about others. I could choose to be completely narcissistic, but ultimately I don’t think that’s a very satisfying way to live. The other makes my life more satisfying and also has the possibility of doing that for others, even though, in the end, we still die.”

“Exactly!” he said with emphasis.

That’s all I needed to hear. A young nihilist with a gentle and generous heart.

4 Comments until now

I am in your debt. Very thought provoking post.

Reading of your conversation and experience with Austin is its own form of guidance, Dr. John. Thanks for this post and for the care behind it.

Believing in a Life after life gives me goals to strive for, desire to help others find hope and purpose, an Anchor in the dark times. If we have only this life, it is easy to become discouraged and cynical. Blessings and prayers.

No inherent purpose to life? Egad man! What would the Bible say? You must be a heretic! Or maybe you just read Ecclesiastes.

The Preacher ultimately decides it is the duty of man to fear God and keep His commandments. What was that commandment Jesus used to talk about? You know, the one with the story about the guy from Samaria. Something about loving your neighbor as yourself?

I think Austin and the Preacher are very much on the same page. Pretty good company for both of them.

Add your Comment!